Name: You Gold

Year:

2023

Material:

pencils, paint markers on paper

Size:

50 x 70 cm, 55 X 65 cm

Support :

Flanders community

[EN]

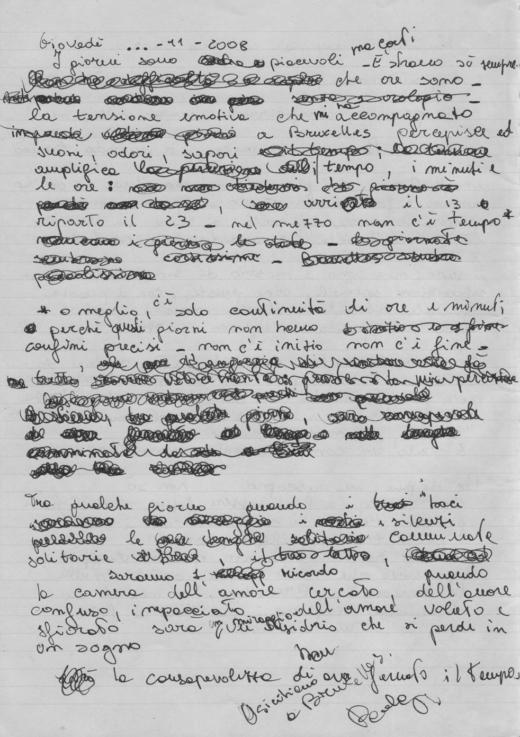

On the one hand, the slap of a few slogans urging us to practice performance, prowess, the total mobilisation of individual and collective resources, this optimisation that can only lead us to success, comfort and wealth. Make it possible, Just do it, Think big, Get rich, do more, High Speed, The beginning of a New Adventure. The other is a series of interviews and conversations that the artist has conducted with men and women suffering from what is commonly known as burnout. Sandrine Morgante explores the field of burnout syndrome, a syndrome that combines profound fatigue, disinvestment in one's professional activity, and a feeling of failure and incompetence at work, the result of chronic professional stress: the individual, unable to cope with the adaptive demands of his or her professional environment, sees his or her energy, motivation and self-esteem decline.

In this new series of drawings, entitled You Gold, Sandrine Morgante literally draws burnout, using injunctions and confidences, slogans and stories of suffering. "The more dysfunctional it is, the more you're caught up in this kind of madness. I'd like to resign, I can't take it any more, I'm suffocating "

Performative graphics, bubbles, black holes, capitals, fonts that are sometimes dynamic and seductive, sometimes choppy and disordered, cries or murmurs, the composition of these poster-sized drawings conveys the shock of words, the loss of self, the systemic explosions and all those individual stories.

Jean-Michel Botquin

www.nadjavilenne.com/wordpress/?p=27661

[FR]

D’une part, la claque de quelques slogans nous enjoignant à pratiquer la performance, la prouesse, la mobilisation totale des ressources individuelles et collectives, cette optimisation qui ne peut que nous amener à la réussite, au succès, au confort et à la richesse. Make it possible, Just do it, Think big, Get rich, do more, High Speed, The beginning of a New Aventure. D’autre part, une série d’entretiens, de conversations, que l’artiste a menés avec des hommes et des femmes souffrant de ce que l’on appelle communément le burnout. Sandrine Morgante investit le champ du syndrome d’épuisement professionnel, désigné par cet anglicisme [ˈbɝnaʊt], un syndrome qui combine une fatigue profonde, un désinvestissement de l’activité professionnelle, un sentiment d’échec et d’incompétence dans le travail, résultat d’un stress professionnel chronique : l’individu, ne parvenant pas à faire face aux exigences adaptatives de son environnement professionnel, voit son énergie, sa motivation et son estime de soi décliner.

Dans cette nouvelle série de dessins, intitulée You Gold, Sandrine Morgante dessine littéralement le burnout, reprenant injonctions et confidences, slogans et récits de souffrances. Je suis tétanisée, j’arrive plus à bosser, toutes ces injonctions contradictoires qui vous tombent dessus, j’ai complètement péter les plomb, plus c’est dysfonctionnel et plus vous êtes embarquée dans cette espèce de folie, J’aimerais démissionner, j’en peux plus, j’étouffe, c’est moi qui n’ait pas réussi à gérer la pression… Graphiques performatifs, bulles, trous noirs, majuscules, polices tantôt dynamiques et séductives, tantôt hachées et désordonnées, cris ou murmures, la composition de ces dessins au format d’affiche traduit le choc des mots, la perte de soi, les déflagrations systémiques et toutes ces histoires individuelles.

Jean-Michel Botquin